A lesson in failing fast

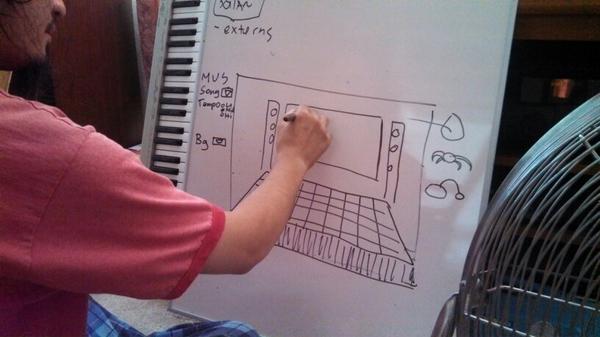

Prototyping on a dry-erase board

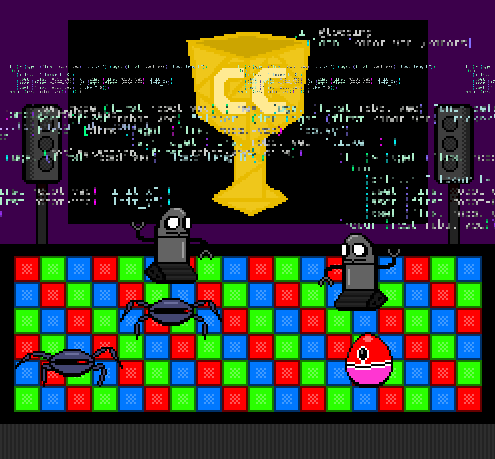

A few weekends ago, Mark and I entered the Clojure Cup coding competition. Our entry was an interactive experience called robot_dance_party.gif. Create a robot dance party in your browser. Export to .gif (we never got around doing that part). Our web app was written in ClojureScript, and the language’s JavaScript interop capabilites allowed us to use jaws.js, a JavaScript library for making HTML5/Canvas games.

Although we received only a few votes from the public and mediocre ratings from the judges, that is besides the point of this blog post. Why this was so important to me was that we made this thing in two days. Our previous game took two years! I’ve learned a lot from these two projects of contrasting time scales.

Super Wizard Potion: the neverending project

Our previous project was also our first video game, an in-browser puzzle game called Super Wizard Potion. On the day of the beta release Mark posted a post-mortem of sorts on Facebook:

I am so burned out of this game. We’re going to let the game sit for a while as we gather feedback, and come back to it after we pursue some smaller projects. In the near future, we plan on focusing on making quick prototypes for games, not spending over a month on a particular idea. That way, we can let our ideas flow and focus on our favorite ones and build on them. By recent months, I started to get tired of SWP, so I want to make sure we focus on projects we feel enthusiastic about.

I’m not saying I don’t like SWP, it’s just that I had so many ideas for it that we had to unfortunately cut out just to get it finished. But hey, this is only our first game! The lessons I’ve learned and the experience I’ve acquired are a great personal investment. My horrible coding was sloppy and huge (first time with a big project in Javascript), but I can learn from the mistakes I’ve made if I decide to make another game in Javascript. I learned a lot about pixel art, and I’ve never seen Kris churn out music so fast before. So even if I’m not super-proud of the game itself, at least we came out with pretty cool art and music.

robot_dance_party.gif: a quick and dirty version 1

In the tech startup world much advice is given to release early and fail fast. In his essay “The Hardest Lessons for Startups to Learn”, co-founder of startup incubator Y Combinator Paul Graham writes:

The thing I probably repeat most is this recipe for a startup: get a version 1 out fast, then improve it based on users’ reactions.

By “release early” I don’t mean you should release something full of bugs, but that you should release something minimal. Users hate bugs, but they don’t seem to mind a minimal version 1, if there’s more coming soon.

Although playtesting became an integral part of the development of Super Wizard Potion, it took us a very long time to get it in the hands of players. By the time of the first round of playtesting, we were already so deep into the development process. We were so caught up in what WE thought the game should be that we were blinded to what first-time players would think of the game or if they could even get into the game at all. After that first round, we began to make drastic changes to the game. We would have saved so much time and energy if we had people play a much earlier iteration of the game.

Powering up for the coding competition with burgers

Contrast this with the end result of the Clojure Cup coding competition. With robot_dance_party.gif we had a working product in two days. We submitted our entry and soon the feedback came rolling in. It didn’t really matter to me that we didn’t receive anything more than 3 out of 5 stars from the judges on any of the criteria. The important thing was that the judges were able to use a minimal yet working application so they can give us feedback.

Failing Faster

Learning from these two drastically different approaches in development, we have since changed focus as a team. Still being beginners in game development, we realize that we shouldn’t be taking on ambitious, long-term projects but smaller projects that would take no more than a month before a prototype is sent off to testers.

Beyond just relieving the pressure of wasting so much effort into a project that would probably fail, focusing on non-ambitious games would free us to take more risks and explore the possibility space of game design before we plunge deep into an idea that we think would be worthwhile investing more time and energy on. To quote Paul Graham once again (from “Before the Startup”):

Starting a startup is like a brutally fast depth-first search. Most people should still be searching breadth-first at 20.

Due to the fact that we are virtually unknown and do not have much of an audience, we even feel somewhat responsible to take more risks with small-scale games. In her book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters, game designer Anna Anthropy writes:

Smaller games with smaller budgets and smaller audiences have the luxury of being more experimental or bizarre or interesting than 12 million dollar games that need to play it as safely as possible to ensure a return on investment. Imagine what a videogames industry that wasn’t fixated on hits–that wasn’t required to make hits–would create.

What if there was a game about a ghost who really had to poop and must haunt a house to find the bathroom? Just wait until Halloween to find out because that’s exactly what we are working on right now!

This ghost really has to go poo.

You can expect some strange little interactive experiences from Plunger Games released more frequently in the near future. Although we do not yet have a website that acts as a portal for our games, you can follow me on Twitter and Mark on Tumblr.

I will leave you with this motivational piece from Extra Credits: